Science fuels farm yields in Shaanxi

Baoji offers modern agriculture model built on research as well as innovation

At the foot of the Qinling Mountains in western China, the future of farming is taking shape not in open fields but in quiet laboratories, where microscopic shoot tips and single cells are driving a shift toward science-powered agriculture.

In Baoji, Shaanxi province, researchers at the city's academy of agricultural sciences are using molecular breeding, gene editing and shoot tip detoxification to develop higher-yielding, disease-resistant crops. Their work is gradually moving the region away from traditional practices and toward a modern agricultural model built on research and innovation.

In one laboratory, a researcher sliced a sweet potato shoot tip measuring barely half a millimeter. "This tiny piece is the origin of all virus-free seedlings," the researcher said. Ridding the plant from viral infection can raise yields by up to 30 percent.

Nearby, scientist Du Xueshi examined tomato seedlings for genes that block the yellow leaf curl virus. "It's like checking their ID," Du said. "Only the plants with the right resistance can thrive in the field."

For farmers, the impact is already visible.

In Qishan county, soybeans once produced about 135 kilograms per half hectare. Farmer Tie Hongke said the locally developed Baodou No 10 soybean variety now yields about 275 kg. "I earn tens of thousands of yuan more each year. It's all thanks to the new varieties," he said.

Baodou No 10, developed in Baoji, contains 43 percent protein and is prized by food-processing companies. Another variety, Baodou 1519, has reached a record yield of 302 kg per mu (0.066 hectare). Sweet potato researchers said their Qinshu 13 strain can yield up to 6,000 kg per mu, while a new short-vine variety allows full mechanical harvesting, cutting labor costs.

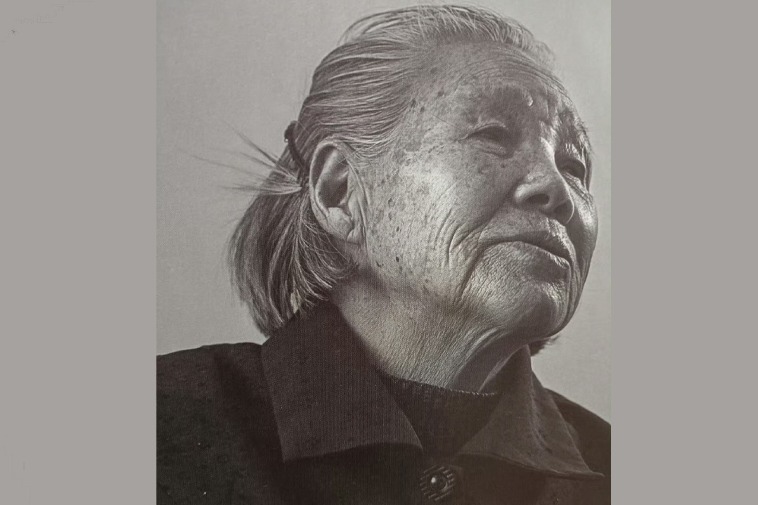

Local cultivators report consistent improvements. "They're tender, fragrant, and each year the yield rises," said Hou Wuzhou, who has farmed sweet potatoes in Guihua village for more than two decades.

Many of Baoji's varieties, including Qinshu No 5, are now planted far beyond Shaanxi, from the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region in the far west to the neighboring provinces of Henan and Shanxi.

Advances in crop science have also accelerated breeding cycles. Zhang Huicheng, a senior agronomist at wheat research institute of Baoji Academy of Agricultural Sciences, said new varieties once took more than a decade to develop."Now, with molecular tools, they 'grow up' in seven or eight years," he said. In rapeseed oil research, single microspores are being cultured into stable lines in as little as three years.

Baoji administers three districts, nine counties and a high-tech development zone. It has become China's largest base for premium kiwifruit and dwarf apple trees, and a major center for alpine vegetables and dairy production.

The city's agricultural output reached 42 billion yuan ($6 billion) in 2024, up from 31.7 billion yuan in 2019, a 32 percent increase over five years, driven mainly by advances in science and modernization.

National policy is moving in the same direction. The recent fourth plenary session of the 20th Communist Party of China Central Committee called for accelerating the modernization of agriculture and rural areas and solidly advancing rural revitalization.

It urged improvements in productivity, the rollout of modern technologies and stronger support for farmers.

Those priorities closely match Baoji's strategy. The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs has also called for developing "new quality productive forces" in farming, from bio-breeding to drones, artificial intelligence and digital management tools, with science playing what it described as a leading role in shaping modern production.

Baoji's breeding work reflects that national shift. The city's biotechnology laboratory, the first of its kind built in Shaanxi, operates six breeding units capable of producing three to four generations of crops a year, significantly speeding the development of new varieties. The approach has already been used to test tomato resistance to yellow leaf curl virus and other traits.

The academy's germplasm bank now stores more than 4,400 samples. "Any one of these could become the next breakthrough variety," a senior manager said.

Wang Zhouyu, president of the academy, said the goal is simple: to grow better crops and put more smiles on farmers' faces.

In a region long shaped by the Qinling Mountains, Baoji's blend of laboratory science and field-level innovation is emerging as a model for how China aims to modernize its agriculture — one improved seed at a time.