Partnership becomes pressure for Europe

As discussions about a possible ceasefire in Ukraine continue, a more fundamental issue has emerged. The question is not only how the war might end, but how strategic choices with far-reaching security consequences are made, and how much leverage European countries exert over those choices.

Several European governments fear that the United States may be prepared to give territorial concessions to Russia without firm, long-term security guarantees for Ukraine. This concern is grounded in experience rather than conjecture. Europe has limited leverage over US strategic choices, even when those choices directly shape European security.

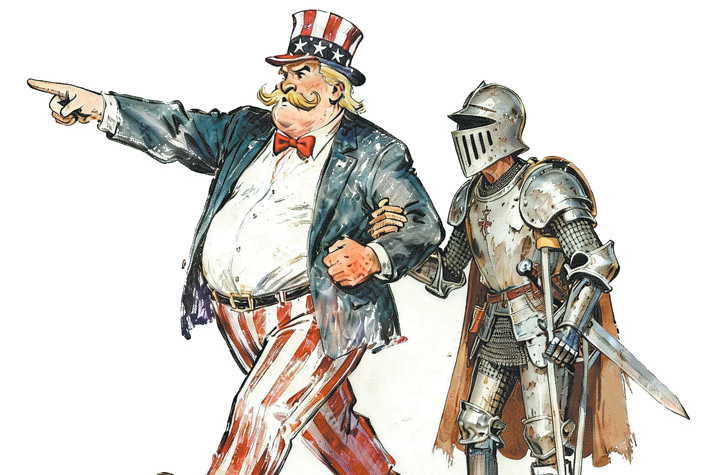

This is not primarily about Ukraine or President Volodymyr Zelensky. It concerns the internal distribution of power within the Western system. Europe relies on the US for military protection, intelligence cooperation and critical technologies. The US does not rely on Europe to the same extent. This asymmetry influences how strategic authority is exercised.

Recent events have made this imbalance more visible. In recent days, senior US officials have raised questions about Denmark's control over Greenland, framing the matter in terms of US strategic interests. These remarks concerned a NATO ally and treated sovereignty as a matter open to discussion rather than as a settled principle.

The significance of the episode extends beyond the specific case. It demonstrates that formal alliances do not prevent pressure when power relations are uneven. Legal frameworks and shared institutions offer limited protection when one party lacks the capacity to resist.

This logic is no longer confined to isolated incidents. In current US policy debates, European governments are increasingly portrayed as slowing or complicating US objectives. Political developments within allied states are discussed as factors that can be influenced in order to achieve preferred outcomes. Coordination remains the official language, but influence is exercised more directly.

The underlying cause is practical rather than ideological. Washington seeks to limit long-term commitments in Europe and to redirect attention toward other strategic priorities. European governments continue to regard Russia as a persistent security threat requiring long-term deterrence. These positions no longer coincide as closely as they once did.

Europe's vulnerability is not confined to defense policy. Defense production is fragmented in Europe. Ammunition output is insufficient, logistics capacity uneven and joint command structures underdeveloped. These shortcomings are well known and have been repeatedly documented. They persist because the decision-making remains largely national, while security risks are shared.

Similar constraints are evident in civilian governance. Many core public functions in Europe depend on digital infrastructure controlled by US companies. Health care administration, law enforcement systems, courts and public agencies rely on cloud services operating under US law. European authorities do not exercise full oversight over how data are accessed, stored or transferred.

European cybersecurity and data-protection bodies have warned about these dependencies for years. The central issue is not technical reliability, but dependence. Control over infrastructure confers influence over institutions.

Political communication follows a comparable pattern. Public debate in Europe takes place largely on platforms owned and governed outside the continent. Their design prioritizes visibility and engagement, which tends to amplify conflict. European regulation focuses primarily on content moderation rather than ownership or jurisdiction. As a result, political discourse remains structurally dependent.

This dependence is reinforced by the close integration of US technology firms with US security institutions. Companies such as Palantir provide data systems to European police forces and public authorities while maintaining strong institutional ties with US defense agencies. Senior personnel move regularly between corporate roles and government positions.

The political effects are tangible. Control over major platforms enables private actors to shape debates across borders. Figures such as Elon Musk illustrate how ownership of communication infrastructure can be used to advance political positions rooted in US domestic conflicts, with consequences for other societies.

From a global governance perspective, Europe faces two interlinked constraints. It lacks the military capacity to act independently as well as technological authority over key institutional systems. Together, these limitations reduce Europe's capacity to shape outcomes that affect its own security and political order.

This should not be understood as a temporary disagreement within the transatlantic relationship. It reflects a broader change in how power is exercised internationally. Decision-making authority is increasingly concentrated, while responsibility is distributed unevenly.

Europe's experience points to a more general lesson. Political alignment with a dominant power does not guarantee equal treatment. Institutional dependence makes pressure easier to apply.

Against this backdrop, it is understandable that many countries have emphasized principles such as sovereignty, non-interference and restraint in international relations. In this respect, China's stated opposition to coercive diplomacy toward partners contrasts with recent US behavior toward its own allies.

The difference in the approaches is quite telling. One model treats dependence as leverage. The other treats sovereignty as a basic condition for cooperation.

For Europe, the implication is clear. Without control over its own defense capacity, data infrastructure and public institutions, it cannot expect equal standing in any system of global governance.

In a more plural international order, autonomy depends on institutional capability. Where that capability is lacking, outcomes will continue to be shaped elsewhere.

The author is a political editor and a regular columnist in the Swedish media.

The views don't necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

If you have a specific expertise, or would like to share your thought about our stories, then send us your writings at opinion@chinadaily.com.cn, and comment@chinadaily.com.cn.