Adaptive co-evolution China’s five-year plans promote the symbiotic development of technology and institutions

China’s five-year plans promote the symbiotic development of technology and institutions

Since 1953, China’s five-year plans have been the country’s key mechanism for guiding economic development. But they also reflect something deeper: China’s distinctive understanding of the relationship between institutions and technology. Western economic development theories, from Douglass North’s institutional economics to Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson’s political economy, argue that institutions must precede technology. According to this school of thought, stable and inclusive institutions are the prelude to innovation and economic progress. Yet China’s trajectory tells a different story. Rather than following a linear path, China’s development has been characterized by the gradual co-evolution of institutional change and technological advancement. In this process, technological progress and institutional adaptation have reinforced and catalyzed each other, jointly shaping China’s modernization.

In the Western tradition, economic modernization is often explained through institutional foundations. The Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom is frequently attributed to secure property rights, functioning markets and parliamentary oversight. The rise of the United States is explained by its constitutional system, open frontier economy and inclusive political institutions. The underlying logic is straightforward: institutions provide certainty, reduce transaction costs and create incentives for innovation. This framework has strongly influenced development advice from multilateral organizations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, which have often prescribed “good governance” and institutional reform as a precondition for growth in developing economies.

China’s early five-year plans (1953-75) reflected a mixed approach, emphasizing both institutional and technological development. The first task was to create a planning apparatus, State-owned enterprises and central ministries that could mobilize resources for industrialization. During the 1950s, China imported large-scale equipment and technologies from the Soviet Union under a State-led institutional framework, which helped lay the material foundations of industrialization. Despite significant investments in heavy industry, the lack of indigenous technological capability meant that much of the industrial system remained dependent on foreign expertise and equipment. The results were mixed: strong in mobilizing resources, but limited in generating broad-based technological or economic breakthroughs.

The decisive shift came in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Under the reform and opening-up policy, China recognized that what the country lacked was not only governance mechanisms but also cutting-edge technology. The introduction of special economic zones, technology transfer through joint ventures and opening to foreign direct investment placed technology at the center of China’s development. These technological inflows, in turn, forced institutions to adapt: legal frameworks for intellectual property were established to protect foreign investors, financial reforms were introduced to accommodate technology-intensive sectors, and education and training systems were redesigned to produce a technologically literate workforce. In China, technological development has become a central driver of institutional innovation.

From the 10th Five-Year Plan (2001-05) onward, China entered a new phase of adaptive co-evolution between technology and institutions. The leadership emphasized “indigenous innovation”, raising R&D expenditure from 1 percent of GDP in 2000 to 2.4 percent by 2020 and establishing 169 national high-tech zones and 115 university science parks. The number of patent applications filed increased sharply from 170,690 in 2000 to 1.1 million in 2015. Meanwhile, companies such as Huawei, Tencent and Alibaba drove technological momentum that pressed regulators to update competition law, consumer protection and data governance. Together, these developments forged a virtuous cycle, in which technological innovation promoted institutional reform, and reformed institutions in turn sustained new waves of innovation.

The 13th and 14th Five-Year Plans (2016-25) marked the clearest articulation of a strategic focus on technology, yet they also underscored the ongoing adaptive relationship between technology and institutions. Strategic sectors such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, biotechnology and green energy have been central policy targets. In the 13th Five-Year Plan, emerging industries were elevated to become a new engine of growth — by 2020, their added value made up around 11.7 percent of GDP — and in the 14th Five-Year Plan, quantum computing, semiconductors, biotech, health, deep space and integrated communications systems were identified as key priorities. At the same time, institutional redesigns have aligned with technological priorities: tax incentives and State guidance funds under the 14th Five-Year Plan were used to direct finance toward innovation. The “Made in China 2025” strategy embodies this approach: instead of waiting for legal or financial systems to evolve organically, it sets out ambitious technological priorities while simultaneously mobilizing institutional mechanisms — from subsidies and patent rules to broader industrial policies — to support and align with them.

In effect, China’s experience points to a more interactive process in which technological advancement and institutional change evolve together. This pattern explains why China’s growth trajectory has been faster and more transformative than many expected. This framework also has global significance. Many countries in the Global South face the dilemma of weak institutions and limited technological capacity, and the traditional advice has been to “fix institutions first”. China’s example suggests another path: invest in technology as the driver of reform. Of course, institutions still matter, but China demonstrates that they can be built in parallel, and often as a response to technological needs. This approach provides a practical model for countries seeking rapid modernization in a world of accelerating technological change.

As China prepares for the 15th Five-Year Plan (2026-30) and beyond, the lesson is clear: the co-evolution of technology and institutions will remain at the heart of development. But the sequence of priority is less rigid than often assumed. AI, green energy and quantum computing are not just scientific challenges; they are institutional ones. They demand new regulatory frameworks, new education systems and new modes of global cooperation. China’s planning system, with its adaptability and long-term vision, is uniquely positioned to orchestrate this integration.

In short, reducing China’s development story to a debate over whether institutions or technology should lead is to miss the point. The success of the five-year plans lies in their pragmatism. As the world confronts new challenges, including climate change, digital disruption and global inequality, China’s experience shows that technological development, when combined with adaptive institutional change, can generate sustained momentum for modernization.

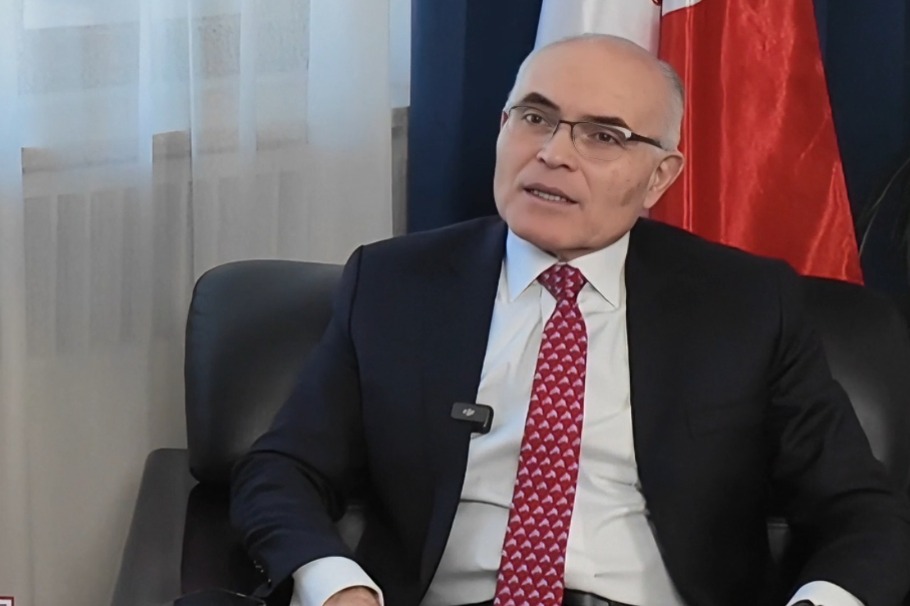

The author is a professor of innovation studies at Liaoning University.

The author contributed this article to China Watch, a think tank powered by China Daily. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Contact the editor at editor@chinawatch.cn.