Coaxing secrets from drifting art

Made-for-export oil paintings offer a rare snapshot of a lost world, revealing forgotten Qing-era wars and reclaiming a historical narrative through overlooked artistry, Zhao Huanxin reports from Washington.

Such episodes likely occurred more than once, but reconstructing them requires painstaking comparison of naval logs, marine accounts, diplomatic correspondence and even missionary records, he says.

The note also explains that the painting's title, The Dutch Folly, was suggested by a story that reeks of mistrust or deception even today.

Chinese officials, it says, had initially granted the British a concession to build a hospital. As the walls rose and portholes were cut, the Chinese discovered the true intent behind the construction.

The officials realized the building was secretly being constructed as a powerful fortified position.

"They at once canceled the concession and indignantly asked 'Sick man yami guns?' or literally — 'Do sick men eat guns?' The fort was never completed," Alex P. Roache, the buyer's descendant, wrote in the note.

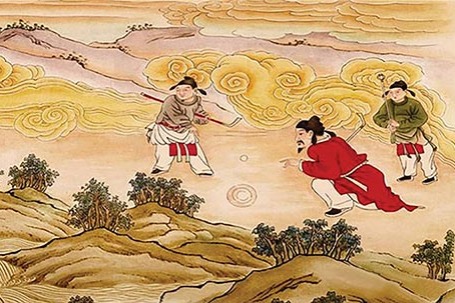

For Kuang, uncovering the story behind the fort paintings is an antidote to the "second injury" of modern Chinese history: the emotional wound of understanding one's past through the eyes of invaders.

In many online Opium War archives, widely circulated images are labeled "painted by British war artists", a curatorial choice that determines whose perspective shapes the narrative and highlights the need to preserve and rediscover China's oil-painting heritage.

"That was a huge shock to me," he says, describing the visceral pain of scrolling through archive after archive of dramatic scenes of "Chinese wooden ships being blown apart by British ships", only to find the works attributed, again and again, to the British side.

For him, the label isn't neutral; it is a warning about what gets lost.