AMATEUR HITMAKER

Meet the man behind the surprise package in the men's volleyball competitions at the recent national games

On a humid afternoon at China's 15th National Games held in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, in November last year, amid the polished ranks of professional youth squads, one team looked unmistakably out of place. Their uniforms were newer than their reputation, their accents unmistakably from the far north, and their faces — still boyish — betrayed a nervous energy more often found in classrooms than stadium tunnels. They were students from Qiqihar No. 1 High School, and they had just done something no one expected: finished fourth in the men's under-18 volleyball tournament, the best result Heilongjiang province had achieved in the event in 66 years.

Standing a few steps behind them, half-smiling and half-reproving, was Bao Changlin. An "amateur" coach only in the bureaucratic sense, the 55-year-old is the unlikely architect of one of the most improbable stories in recent Chinese sports.

Bao remembers the exact date the journey began — June 5, 2005. He recites it the way others recall a wedding or a birth. By then, he had already lived two professional lives: as a volleyball player, and after his retirement, as a bank employee. Volleyball however retained a hold on him. In the evenings and on weekends, he coached children for free, driven by what he describes simply as "not being able to put the ball down".

The summer of 2005, Qiqihar No 1 High School approached him to form a boys' volleyball team. There was no salary, and no guarantee of success, but Bao accepted without hesitation. What he could not have known then was that the decision would bind him to the same gym, the same school and generations of students for the next 20 years.

The early years were austere. Equipment was basic, facilities were limited and the team was regarded as an extracurricular curiosity rather than a serious athletic program. Bao approached it differently though. Drawing on his professional background and his studies at Harbin Sport University, he designed a training system that was methodical, data-driven and unsentimental. Effort mattered, but structure mattered more.

By 2007, the school had secured permission to recruit volleyball-specialty students, gradually expanding the talent pool. That same year, the team won their first provincial championship. They would not lose that title for the next 18 years. The streak was not loud, and it rarely made national headlines, but it established something rarer than trophies: continuity.

Bao's coaching style resists easy slogans. He believes in diligence — players' feet, hands, eyes and mouth must all be "busy", he says — and there can be no complacency. When the team wins, he does not replay their best moments. Instead, he screens the worst match they have played. The idea, borrowed from students' "wrong-answer notebooks", is to cool pride before it hardens into habit. He used the method again before a crucial quarterfinal at the recent National Games, when the team had just crossed the group stage with steady performance.

Individual players receive similar precision. Cao Qihao, now a core attacker, began volleyball late but trained relentlessly. Bao set a single condition: reach a vertical touch of 3.25 meters, and he could switch positions. Cao exceeded the target. When Bao discovered that Cao and his teammates were secretly doing extra training sessions — and risking injury — he stopped them immediately. Discipline, in Bao's view, means knowing when not to push. Today, Cao's reach is 3.40 meters, and he squats 180 kilograms, numbers earned within a carefully controlled system.

What Bao values most, however, is cohesion. Volleyball, he insists, is a social contract disguised as a sport. Arguments are allowed; resentment is not. He intervenes early in conflicts, encourages technical debate, and sometimes even stokes competitive friction during scrimmages so that players learn to resolve tension under pressure. Over time, the team has developed a collective resilience that often matters more than talent.

Off the court, Bao's severity dissolves. Players describe him as a father during training and an older brother afterward. They call him "Boss Bao", or sometimes simply "brother". During holidays, those unable to return home eat at his apartment, crowded around grills and hotpots in a ritual that has become as much a part of the program as conditioning drills. Bao spends freely, amused rather than resentful. For more than a decade, the players have pooled money to buy him a birthday cake every year — reminding him of his own birthday when he forgets it.

Among the most emblematic of his students are twin brothers Zhao Zibo and Zhao Zichun, recruited in 2020 from a rural county. Tall, disciplined and stubborn, they trained without weekend breaks and balanced heavy academic loads with late-night practices. Bao demanded excellence on court but insisted on character first. "If you want to be a star," he told them, "learn how to be a person first." Today, one twin is a primary scorer; the other, a tactical organizer. Together, they are seen as potential future assets for China's national program.

Bao's ambitions for his players have never been limited to medals. Most come from modest families; many entered high school with unremarkable academic records. Bao promised their parents something specific: a good university, a better life. The school placed team members in top academic classes and assigned the best teachers. Bao balanced training accordingly. Over the years, his players have gone on to institutions such as Capital University of Physical Education and Sports, Northwestern Polytechnical University and China University of Political Science and Law. Some have become educators themselves. When professional teams from wealthier provinces tried to recruit his athletes with transfer fees, Bao usually refused. Development, he believed, should not be rushed or sold.

The National Games offered the team an unprecedented opportunity. It was the first time youth groups were divided into under-18 and under-20 categories, and Qiqihar's students were the only nonprofessional squad to reach the final eight. They won three straight group matches, then staged a dramatic comeback from two sets down to defeat a team from Henan province and reach the semifinals. Afterward, Bao told his players, with tears in his eyes, that the bonus money would now cover four years of tuition for one of them. It was not rhetoric; it was arithmetic.

They lost the semifinal to a team from Jiangsu province and finished fourth. It hardly mattered. Their grit drew admiration nationwide, including from the Chinese men's national team coach, who twice sought out the players in the tunnel to speak with them and later promised to visit Qiqihar to watch them train.

Bao, who is also a member of the expert committee of Qiqihar Municipal Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese, is nearing retirement from his bank job. When it comes, he says, he will devote himself entirely to the team. He speaks of volleyball not as an escape, but as a method — of education, of patience and of quiet persistence. His story is not one of sudden breakthrough or celebrity. It is about staying, year after year, in the same gym, believing that with enough care and time, ordinary students can become something extraordinary.

Today's Top News

- China to beef up personal data protection in internet applications

- Beijing and Dar es Salaam to revitalize Tanzania-Zambia Railway

- 'Kill Line' the hidden rule of American governance

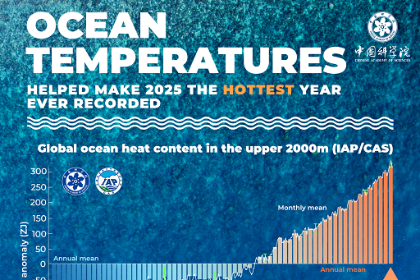

- Warming of oceans still sets records

- PBOC vows readiness on policy tools

- Investment boosts water management